Anders Holen

Pursed Lip, Fan in Hand

15. January - 07. February

ARTWORKS

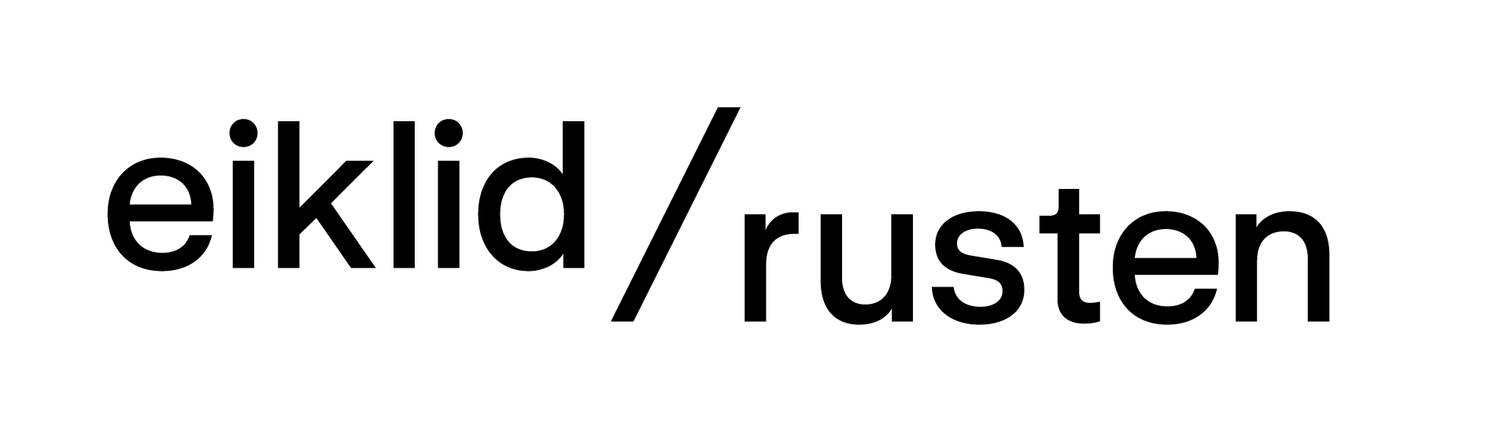

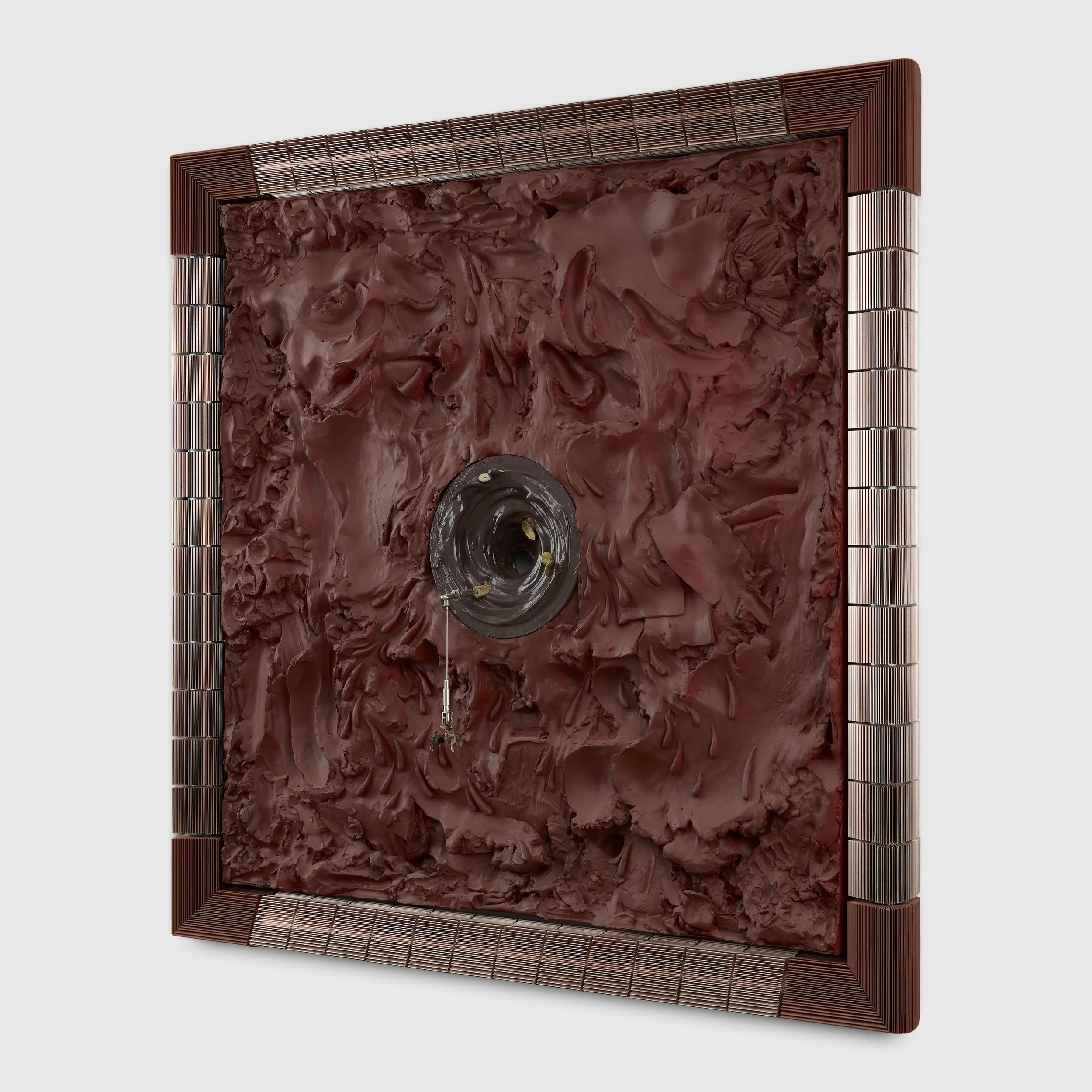

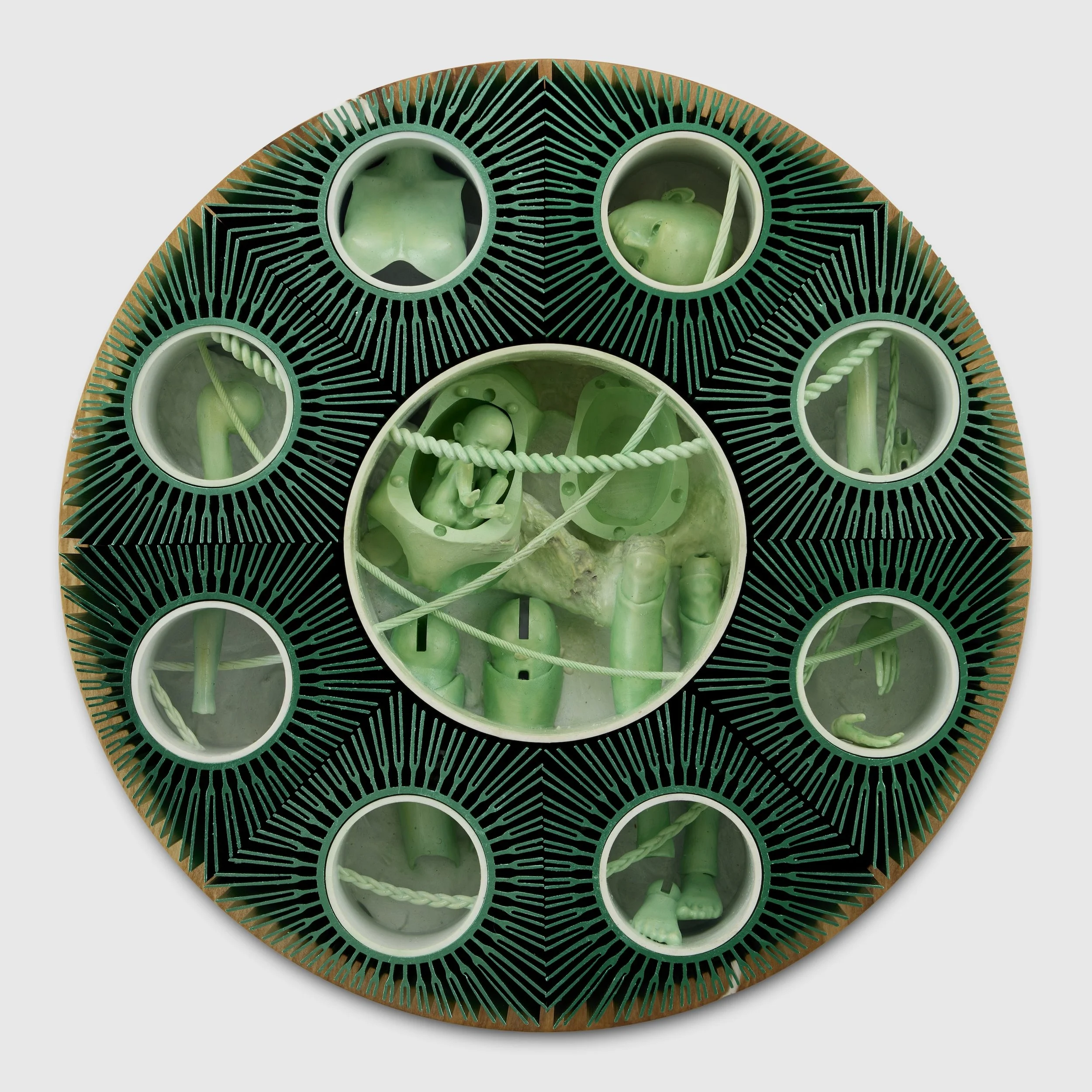

Anders Holen Ick Chronostasis, 2026 Polymer plaster, plexi-glass, glazed porcelain, glazed ceramics, preserved mold, UV-resin, silk, cotton, oil paint, stainless steel, extruded aluminium heatsinks. 140 x 140 x 20 cm

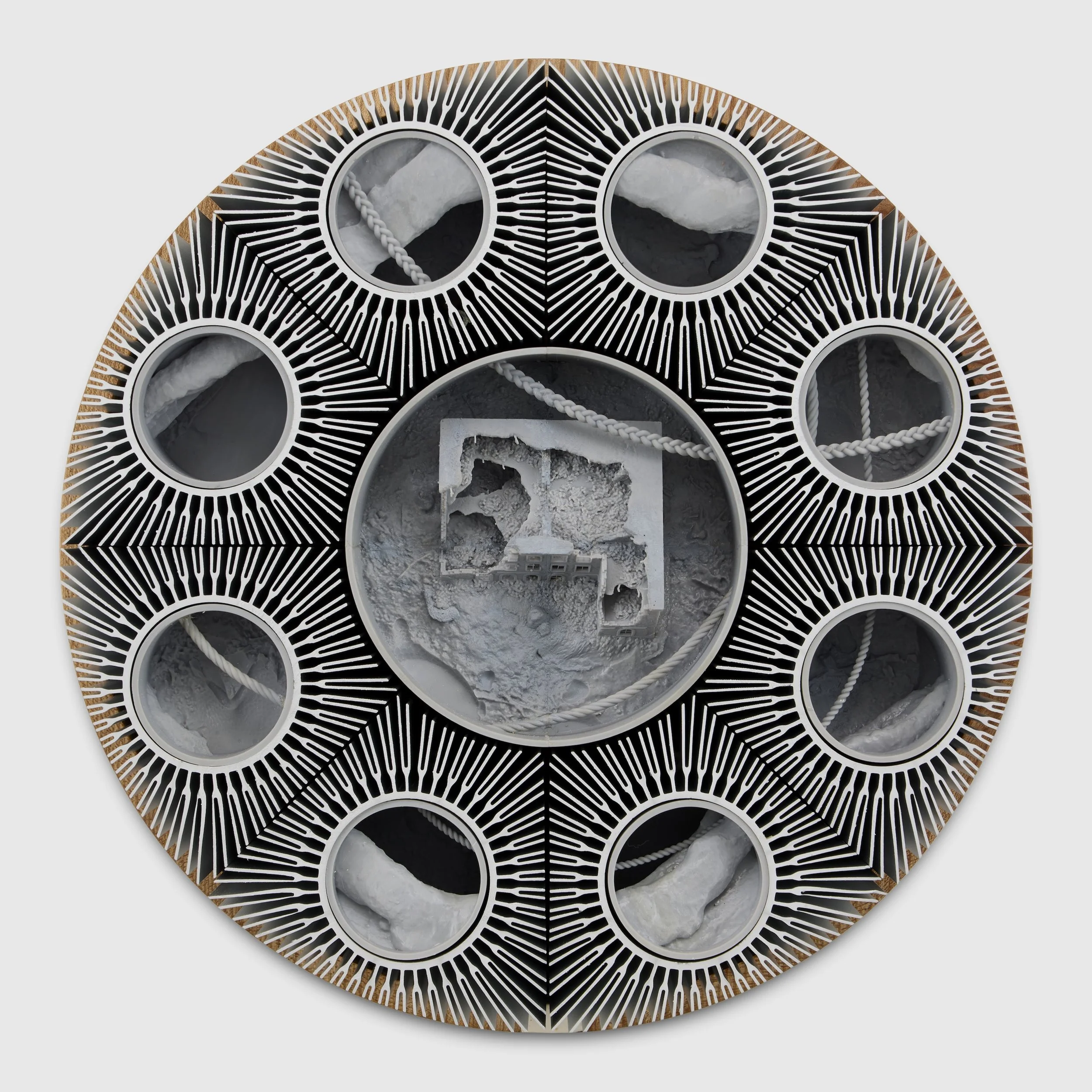

Anders Holen Shuttering Chronostasis, 2025 Polymer plaster, oak, extruded aluminium heatsinks 140 x 140 x 20 cm

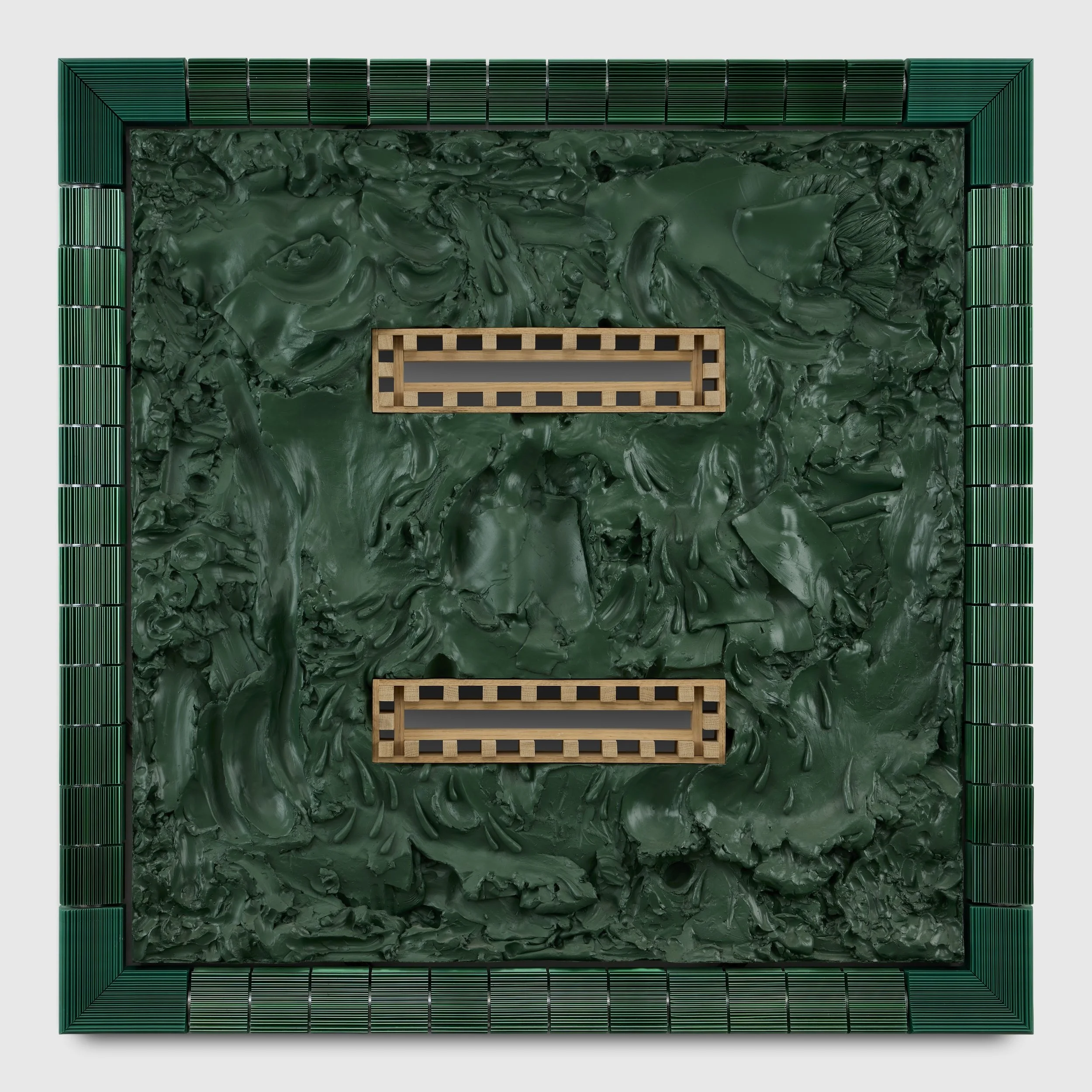

Anders Holen Mealstroem Chronostasis, 2025 Bronze, Polymer plaster, coins, silver birch, stainless steel, extruded aluminium heatsinks 140 x 140 x 20 cm

Anders Holen Unabbreviated Circuit of Agency (Bios), 2025 Bronze, polymer plaster, raw clay, stainless steel, PLA-plastic, UV-resin, epoxy-resin, el-wires, LED-light 102 x 56 x 134 cm

Anders Holen Unabbreviated Circuit of Agency (Logos), 2025 Bronze, glass, polymer plaster, stainless steel, rubber tubes, water, plexiglass, various computer parts 110 x 65 x 135 cm

Anders Holen Stilleben #7, 2026 Signed and dated on the back UV resin, oil paint, extruded aluminium heatsinks, silver birch frame 30 cm diameter

Anders Holen Stilleben #8, 2026 Signed and dated on the back UV resin, oil paint, extruded aluminium heatsinks, silver birch frame 30 cm diameter

Anders Holen Stilleben #6, 2025 Signed and dated on the back UV resin, extruded aluminium heatsinks, elm frame 30 cm diameter

INSTALLATION IMAGES

EXHIBITION TEXT

Enter a room that is catching its breath. In Pursed Lip, Fan in Hand, Anders Holen transforms the gallery into a system where objects do not merely sit. Instead, they respire, circulate, and exert pressure. The exhibition title refers to two physiological strategies for relief: the pursed-lip breathing technique and the use of a handheld fan. These are simple tools used to manage "air hunger" during heavy breathing and moments of distress.

Holen’s practice invokes a philosophy suggesting that we are not the center of reality. Instead, objects, whether a plaster mask, a resin tableau, a plastic wall, or a cooling fin, possess their own "agency" and secret lives. This is physicalized by the architecture itself. Partitioned by walls of recycled, semi-transparent plastic, the room is sensitive to airflow. These membranes tremble as visitors pass, turning the gallery into a fragile, breathing participant that reacts to your presence.

You are greeted by Unabbreviated Circuit of Agency (Bios), a figurative work standing on a simple white plinth. An oversized mask modeled after the artist’s father sits heavily upon a disproportionately small body. The figure appears to struggle under the weight of its own lineage while simultaneously assuming the role of a mischievous puppeteer. Beneath the sculpture, Holen has left the raw dust and casting debris of the studio process. Echoing the studio of Auguste Rodin, where the floor was often strewn with plaster fragments, these traces insist that the artwork is not a magical, polished image, but a material event with a history.

This tension between biological fragility and industrial control connects the works in the first room. In Ick Chronostasis (or The Black Image), a transparent cabinet submerged in black clay reveals a moth consuming clothes, a scene of active decay usually hidden in storage. Nearby, the Stilleben works depict family situations and ruins trapped in resin. Crucially, both series are framed by industrial aluminum heatsinks, mechanical elements designed to dissipate heat from computer processors. In The Black Image, this cooling frame is contrasting the "heat" of rot; in Stilleben, the sharp fins mechanically pierce the domestic scenes. These "cooling devices" assert their own structural agency, intruding upon the intimate moments they are meant to frame.

Moving deeper into the exhibition, the focus shifts to the technological. The kinetic centerpiece, Unabbreviated Circuit of Agency (Logos), bridges ancient myth with modern dependency. Holen reimagines a “perpetual motion” fountain originally designed by Heron of Alexandria in 100 AD. Its form is modeled on the spiraling rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum, where the architecture guides visitors along a continuous, spiraling path. In Holen’s version, water takes the place of people, circulating through the iconic structure. Like the self-destructing sculptures of Jean Tinguely, this work is a poetic paradox. It strives for eternity but is doomed by entropy. The water circulating through its architectural body requires a modern "pacemaker", a mechanical pump, to reset the perpetual motion and keep flowing .

Interacting with the thermal balance of the room are the large, wall-mounted Chronostasis reliefs, known as The Red and Green Images. Like the smaller works, they are framed by the ubiquitous computer heatsinks. These works juxtapose two contrasting energies: the frame itself functions as a mechanical cooling element, engineered to draw heat from whatever it comes into contact with. Within the Red Image, a frozen maelstrom merges with objects whose meaning and value rely entirely on belief. Ground coins and spiritual artifacts become symbols that carry agency through collective trust. The Green Image acts as a visual echo of the red one, sharing the same frame but offering a different kind of containment. Here, the composition is built on the principle of formwork, a temporary structure used to shape flowing material until it solidifies. The formwork constitutes an invisible force, radiating tension as it holds the formless in place.

By making invisible forces such as airflow, gravity, and heat tangible, Pursed Lip, Fan in Hand reveals a network of objects that assert both physical and metaphysical activity. We enter a space populated by many agents, where even the air becomes an active participant. Immersed in such a system, we are prompted to ask: if these objects want something, what demands might they be making of us that we have yet to discover?